One of my favorite parts of VREI is how seamless the transition between theory and practice is. In our second class of the semester, we tackled the process of building user-centered products head on. Brad introduced the class to the concept of design thinking – a technique that most of the cohort was not familiar with. We learned about the importance of building products for the user, and how to actually do it. We also learned how not to develop successful prototypes through learning about design fixation. This occurs when a team either tries to fit an existing solution to a particular problem, or when a team is unwilling to move past an ineffective prototype.

One of the key takeaways for me was that the first step in developing an effective prototype for our target users, the refugees, was to not think about the prototype at all. A blank slate is integral to the foundation of design thinking. It is conducive to building empathy because the blank slate requires that the designer open up to the user without any assumptions, and listen from the heart. The initial intent is to collect as much information about the user, their narrative, and their pain points–specific circumstances in their lives that could warrant the help of a product, initiative, etc. to alleviate that pain. In sum, the aim is to populate the blank slate with effective research. And that is exactly what we did.

I joined a group with four other brilliant cohort members – Jonathan Horowitz, Annabel Smith, Rhys Richmond, and Alya Rehman. Given that this was an in-class exercise in learning about empathy and design thinking principles, we wanted to be as efficient as possible. As such, we hypothesized some of the problems that refugees living in camp conditions would face for the sake of time. When it comes time to actually develop a product, we will rely on the anecdotes provided to us by the refugees we speak to. These anecdotes become a designer’s gold, because the information directly informs the nature of the problem, and in turn, the solution.

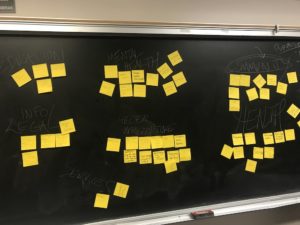

Given our constraints, my group and I populated our slate with various issues a refugee could face, from how to go about seeking asylum, to improving infrastructural capacity, to developing positive community relations. We then grouped our problems by category, as seen above. The final step before moving forward in this user journey was to select a specific problem area, which is exactly what we would do prior to prototyping as well.

The problem area we chose was community-focused, because it was something all five of us were passionate about. We wanted to know how we could help encourage positive social interactions in the refugee camp, an environment often filled with tumultuous emotions and even violence at times. As energized as we were about this realm, it was still premature to start considering a solution. The empathy exercise took a step further by isolating the community-related concerns to a single individual. After all, we could not truly identify any pain points without understanding the user journey.

This journey, an enigmatic term at the surface level, is simply another means of bringing the designer one step closer to the user. My group and I had to build a user persona – a complete profile of someone who would actually enter the refugee camp – to evaluate our own user journey. We conceived an imaginary individual, Said, for our persona, and assigned him an occupation, employment history, family background, demeanor, and various other characteristics that would influence his navigation of the refugee camp environment. We then traced his hypothetical experiences in the camp based on his profile, which allowed us to distill and specify some of the problems related to the community to a person like Said. It was here where some of the questions related to pain points. How could a person like Said be convinced that building a community was important, if he was still attached to his own family? Why should he invest in a community if he believes his stay in the camp is temporary? How can he connect to a group of like minded people if he doesn’t even know where to begin? The questions are endless.

The class came to an end around this point. I found the design thinking process transformative because it forced myself and my group members to be vulnerable, even though Said was a fictional character. We had to think like a refugee, especially in building the user persona, and really consider some of the struggles we would face if we were put in that kind of position. It was my first exposure to this philosophy, and I found it valuable not only to the prototyping process, but also to daily conversation and connecting with people in general.

If we can learn to put our personal agenda and pride aside, perhaps we can foster more intimate relationships by listening from the heart.